One of the realities that every standards professional must deal with is the sad fact that everyone else in the world thinks that standards are…

One of the realities that every standards professional must deal with is the sad fact that everyone else in the world thinks that standards are…

[start over; no one else thinks about standards much at all]

Ahem. One of the things that standards folks must come to terms with is the fact that on the rare occasions when anyone else thinks about standards at all, likely as not it's to observe that standards are…

…boring.

[There. I've said it]

But really, now, this perception has got to change. And with the recent release of Dan Brown's latest pot boiler, The Lost Symbol, I believe I've figured out how to make standards really, really exciting. Really.

Yes, given the reading public’s obsession with probing the backwaters (both real and imagined) of western history for amazing hidden truths, the way is clear to for me to recount a tale of ancient intrigue and power to demonstrate that standards in fact lie at the core of life the universe and everything [sorry; wrong author]. Moreover, in the exciting, surprise ending, I’ll also show that this amazing truth was right there before your unseeing eyes all the time! But unlike the italicizing Mr. Brown, I won’t have to invent anything at all along the way.

The long-unrealized standards secret that I am about to share is this: even the most mundane dynamic and procedural feature of the modern, global process of developing, maintaining, branding and certifying standards has been in existence for almost 1700 years. Moreover, it can trace its lineage to the master plan of a powerful Emperor who invoked the standards process to protect the very existence of his empire from the threat posed by a rogue bishop and his clamoring followers bent upon igniting a standards war.

How’s that you say? Or, as Dan Brown’s Robert Langdon would of course phrase it, "What the Hell?"

Yes indeed, and it shouldn’t take a symbologist to figure this one out. The year was 325 AD, the emperor was Constantine I, the rogue bishop was Arius, and this first global standards conference was the First Council of Nicaea. And, as you’ll see, the analogy of this convocation and its results to the modern standards process is as uncanny as any fictitious historical outtake dished out by Dan Brown. He just makes a whole lot more money when he does it.

So here we go.

In the first few hundred years after the death of Jesus Christ, we are told, the gospel was spread far and wide throughout the western world by his apostles, and then in turn by their followers. Of course, this was a time when literacy was a rare commodity, so the words that spread the Word inevitably varied with the teller and the retelling. Moreover, Christianity was at that time suppressed in the Roman Empire, forcing many of the new faith’s proponents, and their adherents, to spread the message verbally, and in hiding.

Only over time, therefore, was the story of Jesus’ life and teachings written down. Not surprisingly, the facts contained in the various versions of his life that eventually were set down do not always agree. In fact, historians have concluded that none of what we know today as the Gospels were actually written by the apostles to whom they were attributed, and that no first hand account therefore exists.

What we know today as the canonical books of the New Testament are therefore but a selection of the many accounts of the ministry of Jesus that were eventually recorded. Historians also tell us that the Gospels are not representative of the full range of accounts from which they were selected — an inconvenient truth that the emerging faith had no alternative but to address. Of greatest concern to the early Church of St. Peter was the fact that not all of the accounts that then existed agreed on some of the new religion’s most foundational beliefs — including the nature of the divinity of Christ himself.

If this sounds surprisingly like parts of the story line of the Da Vinci Code, it should, because up until this point, Brown’s tale tracks historical fact reasonably closely. But what Brown didn’t mention on his way to best seller success is what actually happened next. Surprisingly, the actual events were in some ways consistent with his far more fancifully concocted story line.

And that was this: upon converting to Christianity, the Roman Emperor Constantine I took it upon himself to help define what "Christianity" actually meant — to come up with a single, empire-wide standard, if you will, that would codify the essential beliefs that defined the new religion, and replace the multiple and potentially divisive belief-specifications that had emerged, based upon the oral histories that had taken root over time. From among these several views of Christianity, he decreed, would come a single belief-standard that, once universally implemented from East to West, would standardize all religious thinking and bind his empire more firmly together.

And so it was that Constantine convened the first global standards conference, inviting bishops from every corner of the empire to gather and apply their wisdom and inspiration to the divination of a singe understanding of the Truth. And come they did, from Libya and from Gaul, from Persia and from Jerusalem, from every Roman province save Britain. Indeed, even from present day Georgia, across the Black Sea and beyond the boundaries of the empire itself.

In the best traditions of modern standard setting, the individuals who answered the call did not have to pay their own travel and lodging expenses (Constantine picked up the tab). Moreover, the all-expenses paid trip took the bishops to a pleasant watering hole at the lakeside city of Nicaea, Turkey, near the shores of the Bosporus and sitting astride the exotic trade routes to the Far East. Notwithstanding the dangers and slow pace of travel in those far-distant times, between 250 and 318 bishops (accounts differ) answered the call out of the c. 1800 then serving, providing broad representation of all populations of stakeholders.

Nevertheless, representation was geographically lopsided, due to the location of the conference, and the reality that there were c. 20% more eastern than western bishops to begin with. The result was that every outcome of the Council was consistent with the positions proposed by the eastern bishops — providing perhaps the first example of regional block voting influencing the final outcome in a global standard setting process.

As is so often the case in standards development today, the starting point for discussions was the submission of proposals from various competing factions. On the subject of the divinity of Christ, for example, the leading candidates for adoption were presented, on the one hand, by St. Alexander of Alexandria and by Athanasius (Jesus was the literal Son of God), and by Arius (Jesus was only the figurative Son of God). Initially, sentiments were split, but, as with the ISO/IEC today, the process was run by consensus rather than majority vote. Near unanimity was eventually achieved behind the literalist submission, and all but two of those in attendance signed the final conference document supporting that position.

The conference attendees also reached other decisions, such as foregoing more straightforward, logical and easy to apply approaches to determine the date upon which Easter would fall each year, and settling instead upon the bizarrely convoluted mechanism still used today (the comparisons to modern standard setting are too painful to articulate).

And what of poor Arius? Just as today, the consequences of losing a standards war can be severe. Arius took his defeat hard, and refused to conform to the new standard. And so he was excommunicated — denied certification as a Christian, because he failed to conform to the adopted standard.

The punishment of Arius thus also provides an early and instructive example of the power of branding in connection with standards. Since the Church owned the brand ("Christian"), once it incorporated compliance to the standard it had adopted to what were, in effect, the licensing terms that licensees (Christians and their priests) were required to obey, the church could deny certification to anyone that refused to comply. "Heresy," after all, is simply a more judgmental term for non-conformance.

Still, Arius was lucky, compared to those that sought to peddle non-conformant beliefs in later days. Over time, compliance testing became much more rigorous, arguably reaching its high water mark during the Spanish Inquisition. In those days, the consequences of telling what even then was probably an ancient joke ("The nice thing about standards is that there are so many of them") could be mortal. Happily, conformance testing techniques and penalties for standards non-compliance are today far more benign than the admittedly often effective, but no longer politically correct, tools of the past, such as the rack, the stake, and the peine forte et dure, or, as it was sometimes more prosaically and descriptively called, pressing.

Despite the unavoidable reality that not everyone’s standard can be adopted, the First Council of Nicaea worked out just fine for most. The conference also turned out well for Nicaea, which apparently gained a reputation as a pleasant destination for standard setting junkets. Six more theological conferences were convened there, with the last being held in 787 — quite a nice run of business, to be sure.

Most impressively, the Catholic Church remained theologically unified around the standard adopted at this first great standards conference for almost two millennia (so far), notwithstanding the fall of Rome and its consequent division between territories east and west, and all of the turmoil in the world in the years that followed.

Indeed, no one seriously challenged this first and most durable of all standards until Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to the door of the Castle Church of Wittenberg, almost 1200 years after Constantine’s bishops returned to their episcopal sees.

And so we see that the practice of standards development as we know it today has a very long and successful history indeed, although you might not have thought about it quite this way until now (confess!) Indeed, it must be admitted that this first great standards conference has been the most successful, if not the most acknowledged, of all to date. Why? Because the standard that Constantine’s bishops adopted by consensus came to be known as the Creed of Nicene. It has been read in every Catholic (and Eastern Orthodox church) as part of every mass ever celebrated, in any church, anywhere, ever since — nearly 1700 years in all.

Rather an interesting, even un-boring standards story, if you stop to think about it. And all true besides.

So take that, Dan Brown.

For further blog entries on Standards and Society, click here

sign up for a free subscription to Standards Today today!

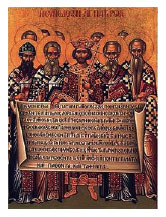

Mosaic of the Emperor Constantine I;

Church of Hagia Sophia, Constantinople